It was a meeting of the minds — three of the world’s most unconventional thinkers in a delightfully conventional setting.

The glow of candlelight. The aroma of fresh oregano.

And the sound of vigorous debate, mixed with occasional bursts of laughter, filled the room.

It was a dinner party with an unlikely combination of guests. One man spoke Greek. Another Italian. And yet another English.

The trio communicated through an electronic translator, worn as an earpiece. Were you to eavesdrop on their conversation, you might assume they were old friends.

However, you would be mistaken.

These men weren’t old friends; they were just old.

One man was born in 1706. Another in 1452. The eldest? 384 BC.

The dinner guests were transported to the future with the help of a time machine.

And they were sitting at my kitchen table.

Despite their obvious differences, the men shared one thing in common: They were polymaths who disrupted the status quo during their respective time periods.

Their names? Aristotle, Leonardo Da Vinci, and Benjamin Franklin.

Obviously, this story is pure fiction. But it’s my response when asked which three historical figures I would break bread with.

Though the characters may change — based on whatever I happen to be reading — my mind always goes to the polymaths. Why? Because the world’s most intriguing individuals have always been “deep generalists.”

I believe that the continued success of today’s organizations, companies, and communities depends on polymaths who think outside the box.

The most innovative developments of the future — in business, science and the arts — will come from creative generalists who blend unique disciplines with technological skill sets.

What exactly is a polymath?

The question is surprisingly difficult to answer. Here’s how the Oxford dictionary defines it:

The word is derived from polumathēs, an early 17th-century Greek term meaning “having learned much.”

When used loosely, the term could apply to anyone with an array of interests, hobbies or knowledge. However, the secondary definition hints at a deeper meaning.

Carl Djerassi, Stanford University chemist and literary author, emphasizes the distinction between “the polymath” and “the hobbyist” in an interview with The Economist:

“It means that your polymath activities have passed a certain quality control that is exerted within each field by the competition,” says Djerassi. “If they accept you at their level, then I think you have reached that state rather than just dabbling.”

Bestselling author and Medium contributor Michael Simmons expands upon this sentiment, defining a modern polymath as:

Someone who becomes competent in at least three diverse domains and integrates them into a top 1-percent skill set.

Despite the world’s immense need for polymaths, these individuals seem to be quite rare.

That’s because society promotes specialization over generalization, based on a long-standing assumption: The more deeply you specialize, the more easily you can find employment.

Another benefit?

Establishing oneself as an expert is profitable. Doctors, lawyers and investment bankers all charge top dollar for their hard-earned knowledge.

Yet, there is evidence our reverence for one-track specialization will soon come to an end.

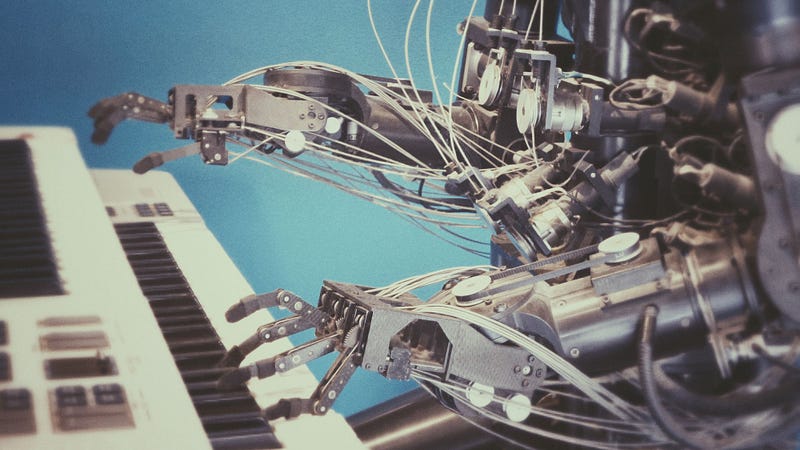

Artificial intelligence will change it all

Experts predict most jobs will, eventually, be made obsolete by artificial intelligence. What roles will be left? Those that require creative problem solving, innovation and humanity.

The AI revolution may be uncharted territory, but the situation itself isn’t unfamiliar.

During the Industrial Revolution, we saw machines replace physical tasks previously completed by humans. This change resulted in the development of new jobs based on cognitive responsibilities.

In many ways, the pattern is now repeating itself; only, this time, jobs are being eliminated by the merging of specialized knowledge with technological skills.

“In 50 to 100 years time, machines will be superhuman,” says Toby Walsh, professor of artificial intelligence at the University of New South Wales. “So, it’s hard to imagine any job where humans will remain better than the machines. This means the only jobs left will be those where we prefer humans to do them.”

In other words, every field imaginable will, eventually, combine with technology to replace a job. Who are the individuals that will make this happen? The polymaths, of course.

Ironically, the majority of mankind’s biggest breakthroughs haven’t come from specialists; they have come from multifaceted individuals.

For example, Nobel Prize-winner Francis Crick credits his background in physics to intuiting the structure of DNA — a problem previously deemed unsolvable by modern biologists.

Richard Feynman, another Nobel Prize-winner, generated his ideas about quantum electrodynamics while watching a guy spin a plate on his fingers in a cafeteria. The realization came after Feynman had rededicated himself to interests outside of physics.

There are dozens of more stories like these, and they all point to the same conclusion: Severe specialization stifles creative problem-solving.

And that is exactly what the modern workspace needs — individuals capable of solving problems by thinking outside of the proverbial boxes that say it can’t be done.

While specialization is important to the advancement of knowledge, it often coincides with a rarely discussed shortcoming: Cognitive bias.

The term refers to the process of overlooking potential solutions because of erroneous assumptions and practiced patterns of thought. At one point or another, we’ve all experienced this in the form of “the bandwagon effect.”

The phenomenon is clearly seen within groups like political parties, religious affiliations, and scientific communities.

HBR contributor and entrepreneur Kyle Wiens agree that overly strict specialization is too limiting. It’s why he actively pushes his team out of their particular roles to continue learning:

“We encourage our technicians to learn programming,” he says. “We even bought a laser cutter to help our designers tinker. Together, we usually discover a solution that we wouldn’t have discovered if we were all stuck in our own little knowledge cubicles.”

At Jotform, we do something similar; our employees work in small, cross-functional teams. Each group operates like a small company and is encouraged to make their own decisions. Not only has the process proven to amplify individual talents, but it’s also made the workday more fun.

While our cross-fertilization has yet to create anything as innovative as biomimicry — an emerging field that looks to nature for solutions to modern problems — some of our best ideas stem from our most well-rounded employees.

“As an investor, if I were going to pick the perfect team, it would be a group of rock-star polymaths with a single subject matter expert as a resource,” says Jake Chapman, founder of Gelt Venture Capital.

As previously mentioned, becoming a true polymath means cultivating deep knowledge in two or more fields. Based on the growing prevalence of AI, my prediction is that, for the majority of future polymaths, one of those fields will be technology.

Thus, the question becomes: How can we find the time to develop expertise in more than one area?

Chapman seems to have found the answer in Pareto’s Principle.

How to become a modern polymath

According to the Italian economist, 80 percent of effects come from 20 percent of causes. In other words, a small amount of work produces the majority of the results.

The principle has several applications, but it’s particularly useful when seeking mastery in something new. For example, polyglot Benny Lewis advises novice language learners to focus on their target languages’ 300 most frequently-used words. Why?

Because these words represent approximately 65 percent of the words used in the conversations they will, ultimately, have.

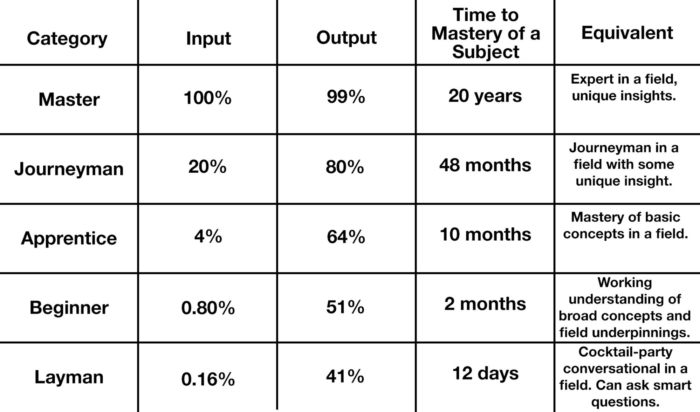

In an article published in TechCrunch, Chapman broke the process of diversified learning into five stages:

The most empowering implication of the principle in action? It’s never too late to reinvent oneself.

For example, a mother who has spent 18 years solely raising a child can quickly reach proficiency in a new field via strategic study. That means she can competitively re-enter the workforce and gain employment, despite a potential career setback.

Additionally, individuals wishing to become modern polymaths can forge unique career paths with the right amount of diversification.

Say someone spends four years specializing in back-end software development, thus reaching “journeyman” status. That person might also wish to reach proficiency in musical composition before blending the two disciplines to create something unique.

Will it be easy? No. But it will be easier than any other time in the history of mankind.

Anyone with internet access and a sincere desire to learn can access abundant information with the click of a button.

Resources like iTunes U, Khan Academy, and edX teach everything from marketing to calculus.

You can even learn to code during your lunch break with Google’s Code University. That’s what Michael Sayman did in high school; today he is the creator of 4 Snap, of one of the world’s top 100 apps.

In an environment of unprecedented technological advancement, we must all embrace our inner polymath to some degree or another.

Those who can combine their skills in unique ways will be tomorrow’s leaders, innovators, and problem-solvers. And they are always invited to my house for dinner.

I can’t wait to see what they come up with next.

Send Comment:

4 Comments:

More than a year ago

Wooooow. You couldn't be more on point!!! Awesome!!

More than a year ago

I must say ¡thank to you! Truly, from my heart. I'm constantly fighting my impostor complex, cause I'm pivoting my career and I'm self-taught. I'm interested in various forms of knowledge (I love to find solutions and share them), but can't seem to be deep enough to consider myself an expert in any field. ¡This article helps!

Now I know I´m a proud Apprentice

More than a year ago

Thank you for sharing this great article ??

THANK YOU(s)

More than a year ago

technical debt is the result of certified generalists, defining done with their limited knowledge.

Issue is not liw or high knolwedge it is about how to apply the knowledge in perfect way in the context and scope of the problem, people, process etc..