Knowledge is power.

It’s a popular phrase — repeated from person to person with little consideration for its true meaning.

Though it’s often attributed to English philosopher Sir Francis Bacon, the expression’s earliest written occurrence appears in 10th-century Islamic literature.

In the Nahj Al-Balagha, Muhammad’s son-in-law, Imam Ali, defines power as authoritative influence:

“Knowledge is power and it can command obedience. A man of knowledge during his lifetime can make people obey and follow him and he is praised and venerated after his death.” — Saying 146

Visit any university campus and you’ll find hundreds of professors lecturing on everything from computer science to theoretical physics to demystifying the hipster — yes, that’s a real class.

Most academics have memorized significantly more information than the average person. Yet, for the most part, society doesn’t consider them to be especially “powerful.”

Obviously, the phrase has evolved to include “increased personal and professional opportunities.”

For example, the more one knows about finance, the more options one has when saving for retirement.

But is more knowledge always better? And does it really make us more powerful? In my opinion, the answer is no.

Due to technological advancements, reaching proficiency in most subject areas is now more attainable than ever before. With 24/7 access to thousands of free online courses, blogs and podcasts, we can advance our education in our pajamas.

However, conversations with friends, colleagues, and family members have led me to believe that consuming information has become trendy to a fault.

Learning is the newest form of “productive procrastination.”

Of course, the irony that I’m writing productivity articles is not lost on me. However, I hope to share a different perspective that encourages strategic action.

Constant reading, researching, and learning can give aspiring entrepreneurs a false sense of accomplishment.

Take Abhishek V.R. He spent two years consuming information about making a website and running an online business before putting his ideas into action:

“I was an expert on everything from social media to copywriting,” Abhishek says. “Take a guess on how much money I made in becoming an expert over the course of two years? Not even a single penny. I didn’t make any money because I never created anything.”

Unfortunately, Abhishek’s story is far from unique. Even experienced entrepreneurs sometimes get stuck in information overload, which shows why sheer knowledge is often powerless.

So, maybe knowledge alone isn’t what we’re after — maybe it’s acquiring just enough knowledge to inform intelligent action.

1. Knowing isn’t synonymous with learning

Big goals often require more than rote memorization; they demand a deeper understanding of core principles. But many of us still associate learning with memorizing facts, formulas, and concepts.

Whether they’re studying Spanish vocabulary words or repeating how “Columbus sailed the ocean blue in 1492,” cramming information is standard procedure for many young adults.

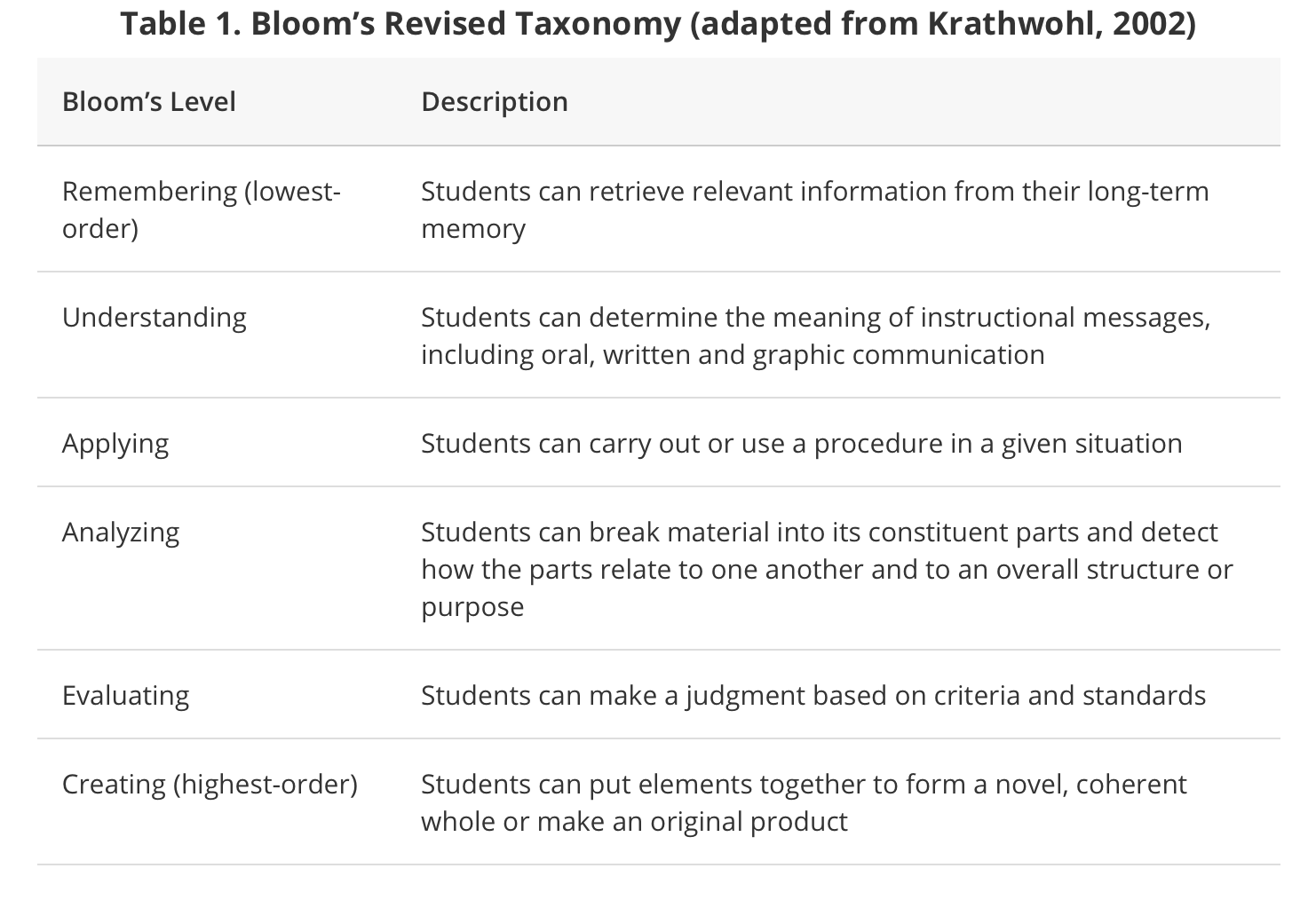

That’s why I was surprised to learn that educational experts believe informational recall is a mere stepping stone to total comprehension. K-12 teachers and college instructors around the globe often plan lessons around something called Bloom’s Taxonomy — a learning framework based on decades of formal research.

According to the taxonomy, the assimilation of knowledge can be divided into six categories:

Despite the fact that total comprehension includes more than reading textbooks and listening to lectures, these seem to be the educational processes that stick with us after graduation.

Perhaps some instructors prioritize rote memorization over creative and logical experimentation, but this tendency also keeps many of us stuck.

Too much knowledge without action leads to overwhelm, discouragement, and misdirection. Eventually, we come to realize we’ve been duped: Knowledge has no power without action.

And, if we’re honest with ourselves, we don’t even remember most of the content we consume.

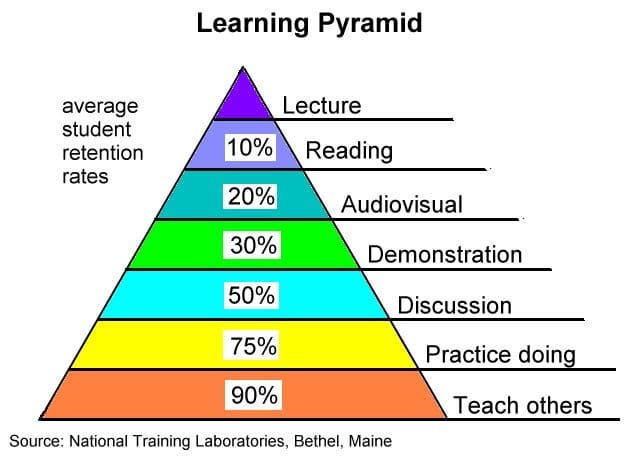

During the 1960s, National Training Laboratories measured student retention rates after 24 hours of varied learning. The organization found that participants retained a mere 10 percent of the information they learned through reading.

Conversely, the students retained a whopping 75 percent of the information they put into action and 90 percent of the information they taught to someone else.

Authors Rena Palloff and Keith Pratt reconfirm this pattern in their book, Assessing the Online Learner: Resources and Strategies for Faculty:

“Assessment that encourages learners to actually do something to demonstrate knowledge acquisition, rather than taking a test or quiz, is not only a better indicator of knowledge acquisition but also more likely to align with outcomes and competencies.”

Whatever knowledge we don’t immediately use, we lose. That’s why the world’s most successful entrepreneurs seem to intersperse knowledge acquisition with creative experimentation.

The process looks something like this:

Read / listen / watch → Do → Evaluate → Repeat

An entrepreneur may then decide to cement their newfound knowledge by sharing it with others.

Obviously, most of us don’t have time to teach a formal class after every book we read. But we could upload a quick tutorial on YouTube; discuss our findings with interested family, friends and colleagues; or even become a mentor for less experienced business owners.

2. Forced learning deflates creativity.

Have you ever seen a child who isn’t self-directed? Consider how much they learn without forced suggestion.

For instance, toddlers watch their parents walk before naturally attempting to do it themselves. They fall several times before getting back up and trying again.

Children don’t feel discouraged by mini-setbacks because they have no concept of failure; they keep trying because it’s fun.

We were all children once. Our natural interests led us to speak languages, learn social cues, and study anything we deemed important. It wasn’t until school that learning became a chore. In other words, learning is natural — until we force it.

“We send them to school and then we wonder why they’re no longer self-motivated, because we’ve taken away the basic motives for learning: curiosity, playfulness, sociability,” says Peter Gray, psychology professor at Boston College.

Gray’s observation is hardly new; it even inspired the 1970s unschooling movement. Coined by educator John Holt, the term refers to a philosophy that advocates learner-chosen activities as a primary means for education.

Not to be confused with homeschooling, unschooling students learn through their natural life experiences. In essence, curiosity drives curriculum. Learning tools include play, household responsibilities, work experience, internships, travel, and educational resources.

“The only reason anyone dislikes learning is because it was made into a chore: something forced and unpleasant,” says unschooler Idzie Desmarais. “As unschoolers, we realize that learning is as innate as breathing. And if learning is never made into something that isn’t fun, then it continues to be something joyful throughout life.”

While I’m not suggesting unschooling as a parenting choice, I think we can all empathize with how bad it feels to force enthusiasm.

As entrepreneurs, we must be brutally honest with ourselves about our motivations: Are we seeking knowledge about a topic of true interest? Or are we acquiring copious information around a subject because we’ve convinced ourselves we must?

The most successful entrepreneurs I know maximize their learning around the aspects of their businesses they enjoy most.

While they do spend time studying essentials of less interest, they minimize acquisition to the bare minimum for action.

3. Sometimes we need to unlearn.

Understandably, most of us view learning as adding knowledge and skills. However, sometimes we have to remove old ways of thinking to embark upon something new.

For example, a husband and wife came to author and Fast Company contributor Marcia Conner to learn how to kayak.

The man knew a lot about canoeing; it was a skill he had spent significant time developing. However, his wife was a water sports novice. And it quickly became evident that the husband’s previous experience was a hurdle to overcome — not an asset.

“He spent his early lessons trying to compare the two types of boats and tried repeating canoe strokes he was certain would work,” says Conner. “As a result, he continually found himself facing the bottom of the swimming pool where our class took place. What he knew already wasn’t as useful as what he needed to learn fresh.”

His wife, on the other hand, made significant progress from day one.

Though much entrepreneurial knowledge is interchangeable, some is project specific. Each business endeavor requires us to challenge our previous experiences. Whether we’re dealing with an unfamiliar industry, an emerging technology, or new team members, we must approach every project with fresh curiosity.

Take Einstein. He never would have discovered special relativity if he hadn’t broken away from Newton’s laws of motion. Nearly every major scientific discovery has challenged an old paradigm.

Unfortunately, approaching new ventures with a fresh perspective isn’t always easy. One way to reduce this tendency is to immediately focus on what makes a new project different than previous ones.

When we proactively ask ourselves why something is different, we break the tendency to run on autopilot. This is a great way to generate fresh ideas, solutions, and perspectives.

4. Sometimes it’s better to delegate

As I’ve mentioned before, the most successful entrepreneurs maximize their time in areas of top interest. As they become more successful, they delegate less interesting tasks to others.

It’s a lesson every seasoned founder understands: There simply aren’t enough hours a day to do everything yourself.

So, why do we even attempt to read every book, listen to every podcast, and watch every TED Talk? If we know we can’t do it all, we shouldn’t be learning about it all.

For example, my company, Jotform creates web forms for time-strapped organizations.

Our developers apply decades of expertise in various programming languages, graphic design, and other web-based disciplines to deliver out-of-the-box functionality.

Someone who doesn’t know how to create forms could spend hours each day increasing their knowledge — or they could pay a small fee for our subscription-based services.

Indeed, there are now so many technology-based solutions available to save us time, energy and money. We live in an era of seemingly unlimited knowledge and service-based resources.

The key to success appears to be regulating our knowledge intake, while putting the information we acquire into action.

The less we obsess about staying up to date on the latest books, podcasts and informational trends, the more time we have to create.

And isn’t that what our five-year-old selves would have wanted?

Send Comment:

5 Comments:

More than a year ago

I just wanted to thank you for this article. It’s exactly what I needed to hear!

More than a year ago

Its important to unlearn what you know.

You can become overqualifed on paper.

A little knowledge is a dangerous thing, rationale ignorance is important.

The doorstep to the temple of wisdom us a knowledge of our own ignorance.

No mans knowledge can exceed his experience. Espitomology.

Einstein said knowledge can get you from A to B but imagination can take you everywhere.

My IQ is 173.

More than a year ago

I think you would like the work I'm doing at Learning Frames.

check it out:

More than a year ago

Great article, as always.

More than a year ago

I have been reading your book post for a while. It get me inspired. Thanks.