“Aytekin! This is why you need to write shopping lists… “

My wife is giving me a (good-humored) telling off.

Absorbed in my thoughts, I’ve managed to forget half the ingredients for the meal I’m cooking our friends tonight.

I’ve always erred on the forgetful side.

But according to new research, this isn’t a bad thing: forgetfulness is not only normal but a crucial part of learning.

Let me explain.

Learning is to the mind what exercise is to the body.

The brain needs to be looked after, fed and trained. Not just once in a blue moon, but regularly — think ‘use it or lose it.’

And having an ‘unstable memory’ helps the brain shed unnecessary content (the way we shed extra pounds before a beach holiday).

It makes the mind more flexible. It increases learning agility.

Learning agility is swift, continuous learning from experience. Agile learners take knowledge from one concept and apply it to another. They experiment and forge connections across different disciplines. And they can ‘unlearn’ information that is no longer useful to them.

We live in an age of extreme information overload; the ability to distinguish value from noise has never been more critical.

Learning smarter, learning faster, learning wider — and forgetting the rest.

Here’s how to build a brain that runs like an Olympic gymnast.

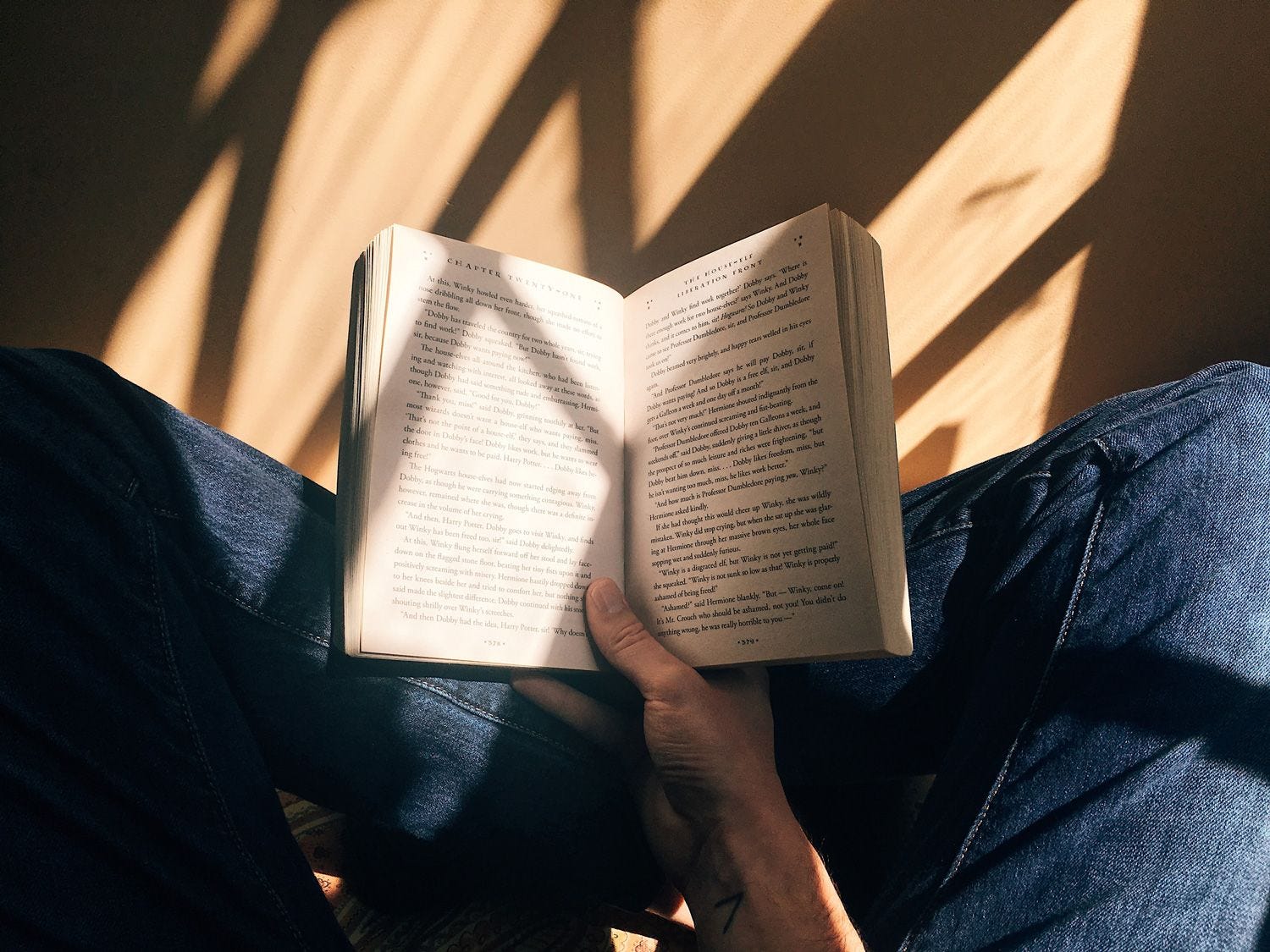

1. Commit to reading (no excuses)

Learning? It doesn’t need to be complicated.

Reading, voraciously, is an excellent place to start.

The world’s most successful people tend to have one thing in common: their thirst for knowledge and their love of books.

Charlie Munger agrees:

“In my whole life, I have known no wise people who didn’t read all the time — none. Zero.”

But where to find time!?!

That used to be my excuse. My life was full with building Jotform and raising a family.

I waited for it to get less busy. It didn’t.

Eventually, it dawned on me: everybody’s life is busy. And everyone has spare minutes in their day.

- Barack Obama reads an hour a day.

- Bill Gates reads one book a week.

If two of the busiest men on earth could carve out the time, what was my excuse?

Now, I’m an opportunistic reader: whenever I see a window, I take it.

I read on my phone, I listen to audiobooks, I flick through papers, I huddle over my Kindle. On the subway, over breakfast, before I fall asleep.

Reading stretches my mind, expands my vocabulary and makes me a clearer communicator. It affects my thinking patterns, the decisions I make and the interactions I have.

If nothing else, it makes me a more interesting person — by transporting me out of the tiny corner of my existence.

“The information we consume matters just as much as the food we put in our body. It affects our thinking, our behavior, how we understand our place in the world. And how we understand others.”

– Evan Williams

In short, we are what we read.

Build up an appetite for knowledge consumption.

2. Make learning deliberate

There are many ways to learn.

Just being alive and adapting to the world forces us to learn constantly. Learning happens to us.

This baseline of learning is accidental.

The second type of learning is conscious.

We consume nuggets of content constantly: by reading the paper, being greeted in a foreign language, or spotting a bird and asking someone what it’s called.

We skim the surface of this knowledge, grazing on information absent-mindedly.

Next time somebody says ‘Cómo está?’ or points to a buzzard, we understand, but not because we made any effort to: it’s simply recognition.

The third kind of learning is deliberate.

It’s focused: think searching rather than browsing. The quality of our attention is sharper.

That’s because we want to have access to what we assimilate; we want to absorb it enough to be able to use it.

This kind of learning leads to recall rather than mere recognition.

It means that we place attention on certain things and ignore others.

When practiced regularly, this generates the ability to create links and transfer knowledge.

3. Learn to learn

Studies show that agile learners are made, not born.

I can vouch for this: I never manage to arrive at recall without repetition. To fully absorb something, I need to return to it — deliberately — more than once.

And then, I need to find a way of putting it into practice.

Deliberate learning relies on a combination of attention, intention, effort and repetition.

This can be summed up as deliberate practice.

Thomas Sterner illustrates this perfectly in The Practicing Mind:

“When we practice something, we are involved in the deliberate repetition of a process with the intention of reaching a specific goal.

The words deliberate and intention are key here because they define the difference between actively practicing something and passively learning it.”

The word ‘effort’ is key. All too often, it’s assumed that this kind of learning relies on talent. Not so.

Dr. K. Anders Ericsson, an expert in the study and science of peak performance, explains:

“People believe that because expert performance is qualitatively different from normal performance, the expert performer must be endowed with characteristics qualitatively different from those of normal adults.

This view has discouraged scientists from systematically examining expert performers and accounting for their performance in terms of the laws and principles of general psychology.”

The effort required for deliberate learning needs to push us beyond our limits.

That feels uncomfortable.

Then again, our comfort zone doesn’t offer much beyond comfort.

Or, as David Peterson, director of executive coaching and leadership at Google put it:

“Staying within your comfort zone is a good way to prepare for today, but it’s a terrible way to prepare for tomorrow.”

4. Space it out

How does deliberate learning work in practise?

Experts recommend you dedicate between 30 minutes and 1 hour per day to learning new material. Any less doesn’t have an impact; any more is too much to take in.

These focused bursts of learning work because they are brief, yet regular. They should take place in your peak hours; as I’ve written before, it doesn’t matter whether these occur at 6am or 6pm.

Resting for a day in between counterbalances the intensity and prepares your brain for the next sprint.

Basically, knowledge is better consumed in bite-sized quantities.

Benedict Carey, author of How We Learn: The Surprising Truth About When, Where, and Why It Happens, agrees.

He compares learning to watering a lawn:

“You can water a lawn once a week for 90 minutes or three times a week for 30 minute. Spacing out the watering during the week will keep the lawn greener over time.”

5. Learn from (and with) someone

People think of learning as a solitary process. It’s just us, our minds, and a book or laptop.

But it doesn’t have to be.

The fastest way to learn is in the presence of others who have already mastered what we want to achieve.

Tony Robbins said it best:

“The fastest way to master any skill, strategy or goal in life is to model those who have already forged the path ahead. If you can find someone who is already getting the results that you want and take the same actions they are taking, you can get the same results.

It doesn’t matter what your age, gender, or background is, modeling gives you the capacity to fast track your dreams and achieve more in a much shorter period of time.”

Learning with, and from, someone is energizing. It sharpens our focus. We are less prone to waste time (because we would be wasting someone else’s time as well).

It’s one thing to have something explained to us on paper or on the screen.

Having something modeled to us fast-tracks us towards grasping what we need to.

6. Cross-train

“Jack of all trades, master of none.”

It’s a well-known saying. And it reflects the conventional narrative that experts only emerge through specialization.

It’s a widely-held assumption that spreading yourself across multiple disciplines means you’re spreading yourself too thin: you’ll dilute your learning and only absorb information superficially.

That’s why most people don’t study beyond their industry.

And it’s also why ‘expert-generalists’ — people who divide their learning across multiple fields — have such an information advantage over those who stay siloed.

Imagine you’re working in SaaS but have a vast knowledge of physics. While everyone else limits their reading to tech publications, you have a wider scope and a unique perspective.

Learning becomes agile when it forges connections across boundaries; transfers knowledge from one task, memory or field to another; and cross-fertilizes.

Elon Musk has been reading two books per day in various disciplines since his teens. His interests span science fiction, philosophy, religion, programming, physics, engineering, product design, business, technology, and energy.

And he has built four multi-billion companies, each of them in a separate industry.

A study of the top 59 opera composers of the 20th century revealed similar findings:

“The compositions of the most successful operatic composers tended to represent a mix of genres…composers were able to avoid the inflexibility of too much expertise (overtraining) by cross-training,”

explains Scott Barry Kaufman, a University of Pennsylvania researcher.

Of course, we can’t all be the new Elon Musk or Stravinsky. But each time we learn something in a field outside our area, we increase our ability to create connections in a way others can’t.

And agile, transfer learning can be a superpower in a world of specialists.

Investing in learning

Learning takes time. It takes effort. It takes commitment.

Why invest your time in acquiring new knowledge instead of clocking more hours at work?

After all, our society values acquisition of money and goods above everything else.

But that’s just the thing: knowledge is becoming its own form of currency. And unlike money, you don’t lose knowledge when you use it. The value of knowledge compounds faster over time.

Learning converts into what money can’t buy: self-esteem, confidence, happier relationships, personal growth…

It gives us a window into the future and the past. It lets us roam across space and time and continents.

It grants us access to the ideas, theories and emotions of the world’s deepest thinkers. This makes life infinitely richer and more colourful.

As Benjamin Franklin once said,

“An investment in knowledge pays the best interest.”

The future belongs to curious, flexible minds.

(And it’s OK to forget the milk sometimes).

Send Comment: